Now that I don’t preach every week, I like to listen to YouTube sermons from other preachers across the country and around the world. So I was interested to hear what some of my colleagues might say about today’s gospel lesson from Luke, chapter 6, verse 27-38. In this lesson, Jesus has just finished speaking the Beatitudes (which in Luke’s version also come with woes! Woe to the rich, the full, the happy, and those who are spoken well of. Jesus doesn’t think much of those folks.).

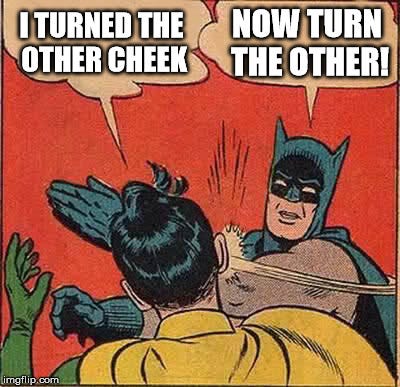

And Jesus then doubles down on the cost of discipleship: “Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you. If anyone strikes you on the cheek, offer the other also; and from anyone who takes away your coat do not withhold even your shirt. Give to everyone who begs from you; and if anyone takes away your goods, do not ask for them again. Do to others as you would have them do to you.”

Is Jesus telling his followers to be pushovers? To just lie back and take it? To accept whatever comes at them and not call it out for what it is—violence, hatred, repression, evil? I heard one sermon today that implied something like that, a sermon that suggested—at least the way I heard it—that Christians should not protest or resist evil. That we should just suck it up and let everyone have their opinions (even if those opinions hold that refusing humanitarian aid or bailing out on allies or eradicating our democracy is really great and we should do more of it), and if people have “different opinions from us” well, we should just love them up. Even while they are celebrating, even encouraging, chaos, oppression, and cruelty.

It was a kind of both-sider-ism sermon, a sort of “there are very fine people on both sides” sermon. What made it worse is that it was delivered to a congregation that included immigrants as well as a sizeable population of trans and queer folks—those who feel most directly under siege right now. It just felt tone-deaf to me. But maybe that’s because I’m a woman, and I know how relentlessly these sorts of Bible passages have been used to keep those lower on the societal hierarchy in line. Wives, is your husband beating you? Turn the other cheek. Slaves, is your master beating you? Turn the other cheek. Love your enemy. Shut up. Lie back and take it.

Well, I don’t think that’s what Jesus was talking about when he said, “love your enemies and turn the other cheek.”

I don’t think he meant that evil had some kind of false moral equivalence to love and kindness, and that really, we should just listen and try to understand why some people like to wield power and oppress others.

I don’t think Jesus meant we should refrain from calling out those who want to silence and suppress. After all, Luke’s gospel has an incessantly intense focus on justice, and on a preferential option for the poor, and on radical inclusion of those traditionally cast to the margins.

So, Jesus--as Luke portrays him everywhere else in the gospel--cannot possibly mean that those ground under the Empire’s boot, or the dainty sandals of the wealthy, or the judgmental feet of the religious authorities, should just “try to see it from their side.”

I think Jesus meant that we should acknowledge that evil is real, and that love and nonviolent resistance is the only way to resist real evil. Many commentators on this passage have pointed out that the behaviors Jesus calls for actually highlight that it’s evil happening. You slap me on the cheek? Well hit me again. I’m not going to sink to your level. You took my coat. Here’s my shirt. Now I’m naked and everyone can see what a brute you really are.

It’s the kind of behavior used by agitators in the civil rights movement—sit at the lunch counter till they drag you out, or walk across the bridge you aren’t supposed to cross and let the world watch the police beat you and the dogs bite you. Shame them by your acceptance of their cruelty.

It’s practiced, intentional behavior that exposes evil and brutality for what it is, without sinking to the level of the oppressor. It’s like the story about Bishop Desmond Tutu, during the time of apartheid in South Africa. Bishop Tutu was walking down the street, when a white man blocked his way and said, “I don’t move for gorillas.” “Oh, but I do,” the bishop replied, and stepped aside and waved the man along. [1]

Cheek turned. In the cheekiest manner!

The love in this love of enemies is not pushover love. It’s not the love of one who is willing to be abused. It’s not the love of one who abandons their own human dignity. It’s the love of one already knows their own worth, their own belovedness, and who understands that deep under the cruelty and violence they are experiencing is another, equally worthy and beloved human being. And the only way to deal with that kind of human being is to reveal the powerlessness and stupidity of their hateful acts. Through loving, nonviolent resistance. Not acceptance. Resistance.

Fanny Lou Hamer, that noted civil rights leader, once said, “we are not fighting against these people because we hate them, but we are fighting these people because we love them.” Loving your enemies does not mean tolerating their injustices. It means hoping better for them. Believing that God also hopes better for them. But it also means demonstrating how far they have fallen from what God hopes for them.

That’s what Jesus teaches, all the way up to his final demonstration of the power of nonviolent resistance, when he hangs on a Roman cross, exposing Empire and religious fundamentalism and oppression for the empty powers they really are. Jesus is no pushover. He does not lie back and take it. He walks straight into it, refusing to be crushed by it. And in doing so, he cracks open our world’s most cherished illusions: that might makes right or that God would ever, ever, ever be on the side of hatred and oppression.

[1] Quoted in Walter Winks’ Engaging the Powers, Augsburg Fortress, 1992, p. 191.

Something I am struggling with in these times: when shame is used by oppressors as a point of pride and that shamelessness turned to be used as a cudgel against others, how do we respond? The relentless "shaming" of Internet has made the idea of "shame" something entirely different than it once was. From social media influencers ("see how perfect MY life is?") to dark hate-filled trolls in the comments, the Internet has made shame a different thing than it once was. Now we can "shame" anonymously (although the response is far too often personal and dangerous). When denial of any shared truth other than a hateful rhetoric and embracing of the shame for those views is considered a point of pride and a sign of "strength", how does one stand up to that?

There is a cartoon going around of a man standing in front of a line of Tesla trucks, similar to Tiananmen Square. While it is a demonstration of courage and individual morality, it did not work out well for the citizens of China as they tried to stand up to their oppressive government. I fear we are seeing "resistance" as doing things that may be futile. Are there other methods of strong, compassionate resistance?

I appreciate the deeper understanding you've offered to this Biblical passage. I've felt palpable anxiety over disruption and chaos that's taken place since Jan. 20. Lives here and globally have been struck hard not just on cheeks but in their whole being. We may do well to engage in spiritual Ta'i Chi in turning aside to let fools pass. Another Substacker, Olivia of Troye, who left before the T-1 crumbled, offers five non-violent resistance points that I believe underscores this message - Jesus wasn't a pushover, and neither should we be. @GretchenSmith505405